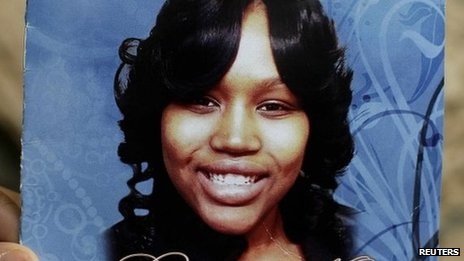

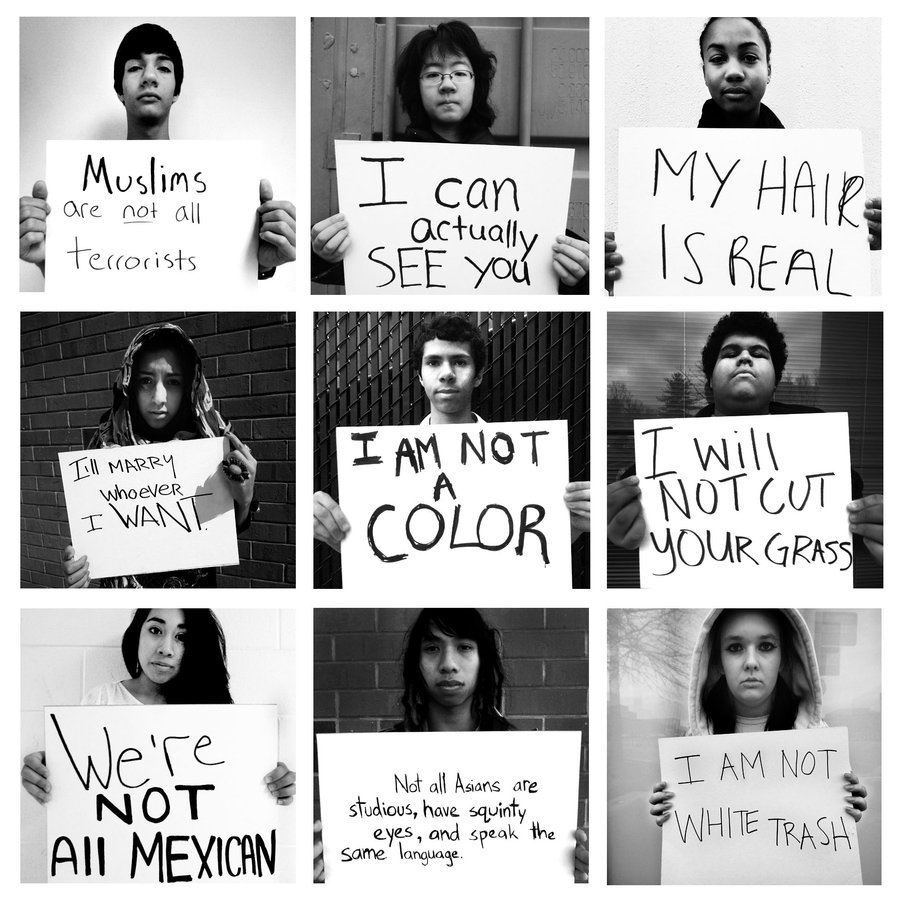

| Are we? Are we really? In a world where a 17 year old boy is murdered simply because he fit the racial profile of an apparent thug, I very much disagree. If race is no longer an issue, this would not have happened. Yes, America has hit a milestone in its history by electing President Obama, just as it did when it finally abolished that last of its local laws prohibiting interracial marriage, but as much as this hints at an end to discrimination we only have to take to the streets to see that this is not the case. The image opposite is a picture of Trayvon Martin, taken not long before he died. As much as the media used an image of him at age 12 to drum up sympathy for the case, this makes a far better point. Young, black and fitting the image of a troublemaker from his hoodies to his hand gestures - and yet he did nothing wrong, he was shot for no reason other than the fact that he looked the part of someone up to no good. Below him is 19 year old Renisha McBride, who had the nerve to knock on the door to ask for help after a road traffic accident. The man who lived there shot her through his screen door. If we are living in a post-racial era, an era of tolerance and equality, why are these blameless young people no longer with us? The answer is glaringly obvious. As much as we try to hide it, as much as we would like to believe we have moved on from the stigmatisation of non-white races, racism still lives on. | | Bibliography

| As much as this is largely an essentialist argument, I personally think that it is very difficult for a white director to do justice to a black narrative, because he has not lived the life necessary to get a black message across. This is in the same way that a man cannot make feminist film, because as much as a person tries to get the minority voice heard, unless one is from that minority he cannot truly appreciate the struggle he is trying to depict, and so it is impossible for them to make as much of an impact as if the minority voice was allowed to represent itself. But as John Singleton (2013) said in his Hollywood Reporter article "Its as if the studios are saying; "We want it black, just not that black."" He means that as much as white directors may struggle to give an accurate account of black life, the gritty work of black directors does not sell well for Hollywood, and so they do not want it. | "Its as if the Studios are saying; "We want it black, just not that black""

- John Singleton | Bibliography

| To really understand the Ghetto, one must first understand that it is firstly and ideology rather than a place. It is music, dress, style, language and hand gestures (Keyes, 2002, p1) as much as it is trailer parks and welfare cheques. Yes, there are many places that are considered ghettoes, but not all perpetuate an unapologetically black voice that calls for recognition of the disadvantaged working class and dismisses the thoughts of previous generations that the life of a middle class buppie was something to aspire to. This is the Ghetto that will be explored and discussed in this post. | | Hip Hop music is a huge part of the ghetto lifestyle, and for many is the only way to get a glimpse at an underclass that is only really open to working class black youths. The music took off in the 1980s with a cultural shift from party music, and by the late 80s rap had several sub-genres which made it in a league of its own. Gangsta rap, Hardcore, G-Style and G-Funk are just a few kinds of rap that emerged from the climate of cocaine and police oppression that plagued black neighbourhoods such as the Bronx. This differed from the musical output of artists like Run DMC and De La Soul in a very important way: it was truly ghetto. Run DMC and the like were not raised in the lifestyle. They were mostly college educated, with middle class families and a certain wariness of inner city kids (George, 2001, pp 95 - 96) whereas the likes of NWA were home-grown, ghettocentric artists who could illustrate the real problems of the black working class. The ghettoes spawned these causeless rebels (Billson, 1996, p91) because of the lack of opportunities offered to children in these areas, and its no wonder they turned to hip hop culture as an outlet.

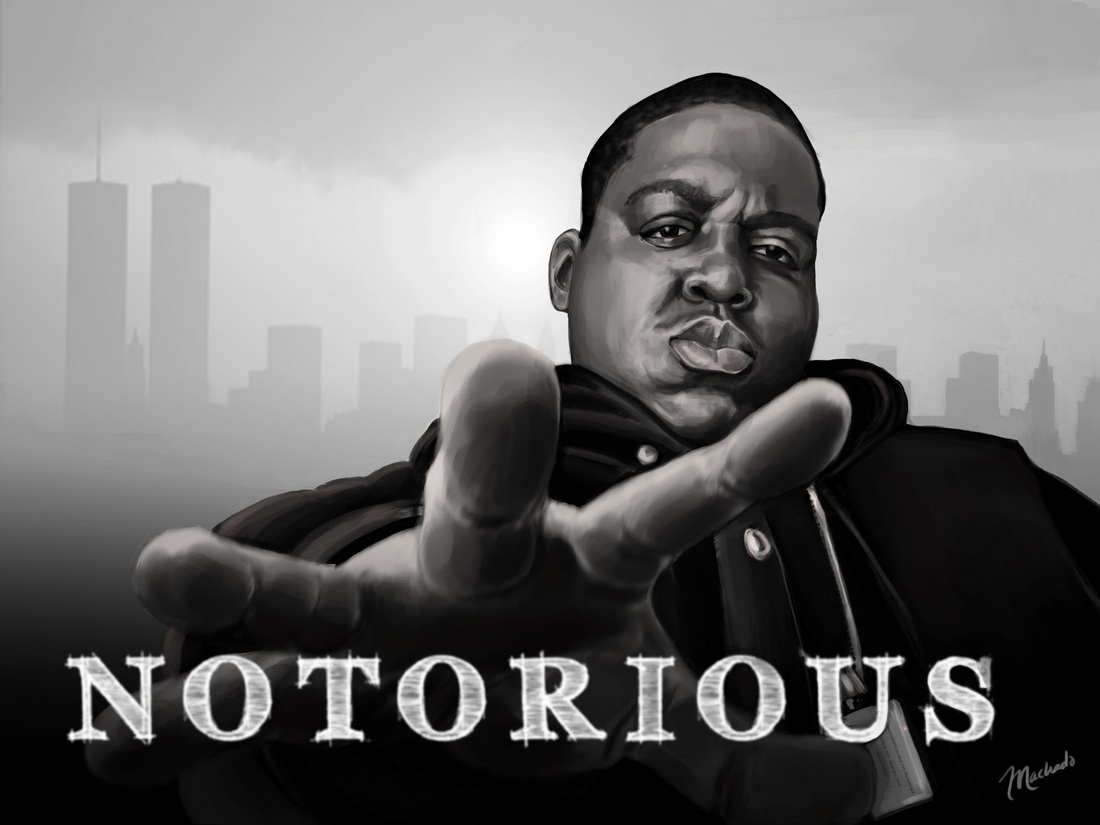

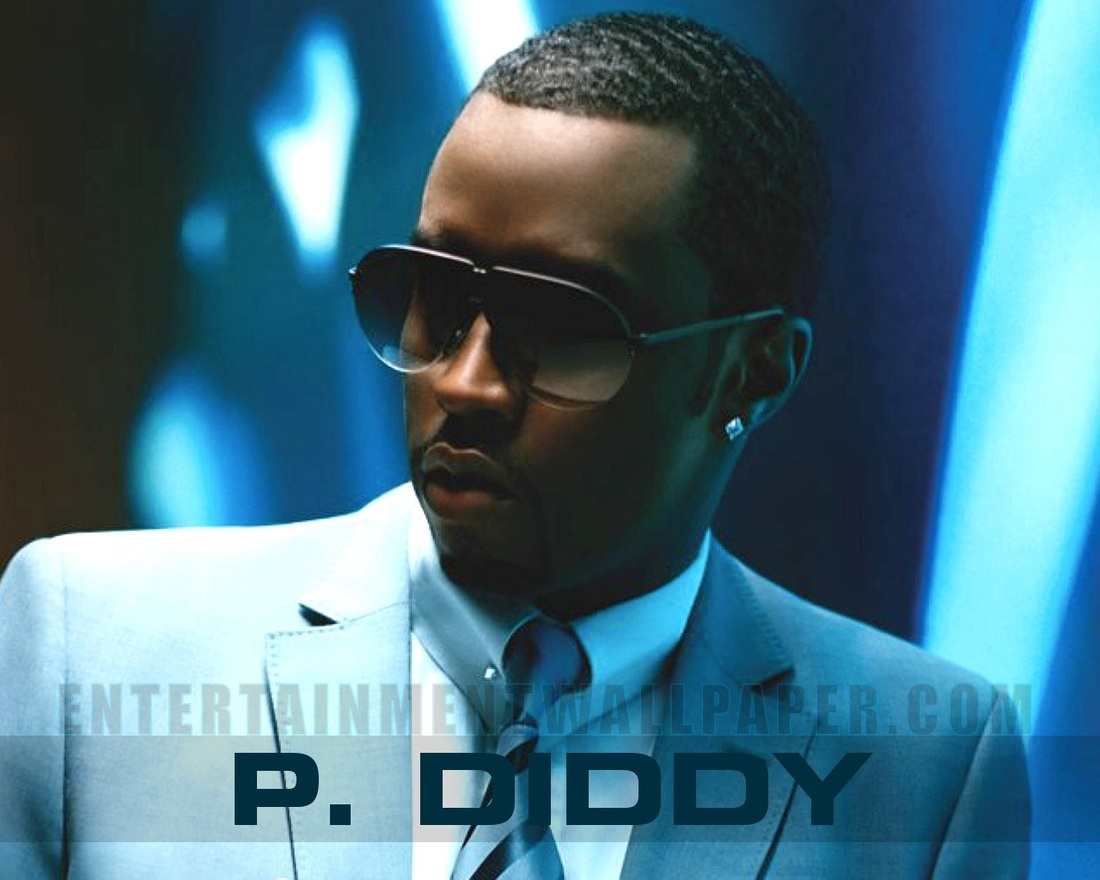

East Coast vs West Coast Rivalry The Bronx, dubbed "the multicultural happening" (Thompson, 1996, p214) of the East Coast, is considered the original home of rap. Its flagship rap-based record company, Bad Boy Records, boasts the ownership of deals with early legends Run DMC and the Beastie Boys. Tropes of those signed to the label are Afrocentric themes of peace and getting back to the African roots, and often make references to social inequalities in their communities with clever wordplay and sampling. | Death Row Records, on the West Coast, have an altogether different approach to their eastern cousin. Fuelled by outrage at the treatment of Rodney King by the LA police, they use their lyrical talents to incite hatred and violence towards figures of authority, as well as filling their releases with misogynistic, homophobic lyrics and videos in an attempt to counter the crisis of masculinity felt by unemployed men in their neighbourhoods. | It can clearly be seen in the above images the difference between the east and the west. Whilst all four images of the artists are glossy and magazine worthy, Biggie Smalls and Puff Daddy have a far more sleek, polished image; whereas Tupac and Snoop Dogg show their street gang allegiances with their far more "street" style of baggy trousers, chunky jewellery and abundant tattoos. Additionally, the following videos make it clear which artist is from which side without the need for them stating it in the song, with Puff Daddy focussing on getting his socially concious message across compared to Snoop Dogg advocating drink, drugs and promiscuity. Interestingly there seems to be a feeling of brotherhood between artists of the same company, as Puff Daddy released "I'll Be Missing You" (a sampling of The Police's 1983 hit "Every Breath You Take") shortly after the murder of fellow Bad Boy artist Biggie Smalls in 1997. Gangsta films, also known as New Jack Cinema, follow in genre the topics the rap music typically depicts - Crime, guns, violence and drugs - and are commonly coming of age stories with a moral message to reject ghettoisation and become educated model citizens. However these films are not always made by black film-makers and so are often criticised by the black community for their Hollywood aesthetics even if they do depict real concerns of communities living in gang controlled areas. Nevertheless, these narrative are as dominated by men as the hip-hop genre is in music. They are male genres, depicting the lives of black men and always show a hyper-masculine community that objectifies women - again, just as rap music does. Together with these films and the accompanying music we could be forgiven for thinking that all black men are ensconced in a culture of crime and gang violence because the media produced certainly perpetuates that myth, but the actions of these supposedly gangsta men outside of the media they produce tells a very different story. Rappers in Politics Considering the militant, socially concious standing of most rappers, it is natural that they were, and to a degree still are, outspoken about politics in the media. however, the days where bands like NWA are rebuffed by those in charge in America, today we see artists such as Jay-Z and Kanye West showing their support for those currently in government, Jay-Z in particular having been quoted in magazines such as USA Today and NME as saying he has a good relationship with President Obama, something which did not occur with previous white presidents. He even made a point to plug Obama's re-election campaign in his 2012 tour, undoubtedly helping to secure the President's victory by boosting the youth vote. This modern take shows us that as much as rap is associated with a criminal underclass, there are modern rappers who worked their way up from the ghetto and very much dispel the myth that the black man is violent and uneducated. Bibliography Billson, J.A. (1996). Pathways to Manhood: Young Black Males Struggle for Identity. New Jersey: Transaction Publishers. George, N. (2001). Buppies, B-boys, Baps and Bohos: Notes on Post-Soul Black Culture. New York: De Capo Press Jackson, D. (2013, 11th July). Jay-Z: Yes, I text with Obama. USA Today. Retrieved from: http://www.usatoday.com/story/theoval/2013/07/11/obama-jay-z-texting-radio-interview/2509283/Jay-Z: "I get texts from President Obama, of course". (2013, 11th July). NME. Retrieved from: http://www.nme.com/news/jay-z/71377Keyes, C. L. (2002). Rap music and street consciousness. Great Britain: University of Illinois Press Thompson, R.F. (1996). Hip Hop 101. In E.C. Perkins (Ed.), Droppin Science: Critical Essays on Rap Music and Hip Hop Culture (pp 211 - 219). Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

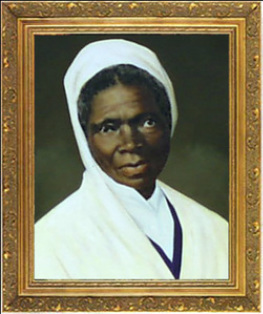

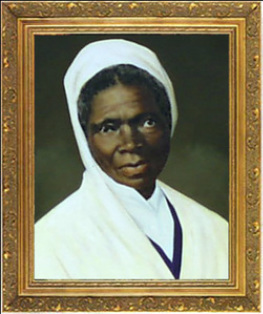

The title of this particular post is somewhat different to its predecessors because it does not necessarily pose a question to answer, more that it poses an age old question that highlights the important cross over between civil rights and women's rights. The question "Ain't I a woman?" was posed by Sojourner Truth, an abolitionist and former slave from rural New York, in her speech delivered to the Ohio Women's Convention in 1851. During her address she made the point that men often say that "women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere." (Truth, 1851), however black women are expected to be as hard-working and strong as both white and black men and are not given these such courtesies that white women enjoy. |  Isabella Baumfree, or as she was better known, Sojourner Truth. Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud-puddles, or gives me any best place!

And ain't I a woman?

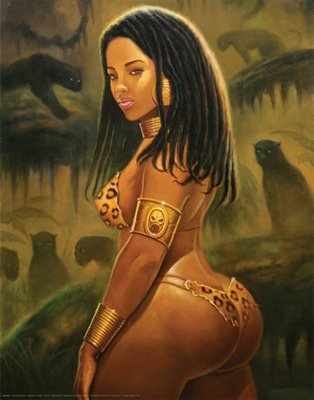

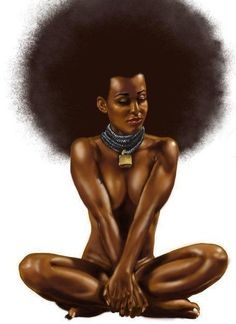

-Sojourner Truth | The above is interesting because of the fascination white men have historically had with black women. They are portrayed as being the sensual, erotic "Other" that Gayatri Spivak discusses in her paper Can The Subaltern Speak? She makes points on human labour an class mobility (1988, p 26) that apply well to the black woman because she is expected to perform as her male counterpart would, however appears to have less mobility even within the context of slavery because male slaves are merely labourers, whereas female slaves are expected to do all the things the men have to do, and are then raped at the leisure of her master for her efforts. She is denied all aspects of dignity and watches her children sold on to new masters even as she faithfully serves her own; and yet male slaves work the fields and have it comparatively easy. She goes on to state that the black woman with little to no money is the ultimate subaltern because she appears to have so little to offer rich white society, and therefore has no voice. Even in the context of America after the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery there was little change in the life of the black woman until the Civil Rights Act of 1964 where it was outlawed to discriminate against a person not just on their race, but also gender. Despite these political advances, black women still found themselves fetishized, as if their identity as a woman was solely connected to their bodies. We hear plenty about how black women are thought of first for their hair, lips, breasts and buttocks; and beyond this they have stereotypical links to the supernatural. The character of Epiphany in Angel Heart (Parker, 1987) is one such example. When we first meet her she is washing her hair, and as she converses with the main character we also see that the water has made her white shirt mostly see-through, exposing her braless breasts. For a character who seems younger than she is it is quite shocking, and even more so to see her in later scenes performing a voodoo ritual where she dances seductively and covers herself in the blood of the chicken she has sacrificed. The same can be said of Mozelle in Eve's Bayou (Lemmons, 1997), a beautiful psychic who covers her voodoo based talents with Christian overtones to prevent suspicion in her affluent neighbourhood, though she is honest about the origins of her power with those closest to her. She is quoted by a woman with similar talents to be a black widow, and she is cursed to have her husbands die, no matter how many times she marries. We know at this stage that Mozelle has already loved and buried three husbands, so her apparent curse is very believable.

A case could be put forward that Mozelle suffers in this way because of her close relationship with the supernatural, and the same can be said for Epiphany with her eventual grisly death. Since voodoo is often portrayed as "other" if not strictly evil, we can see why a western film aimed at western audiences would portray traditional African faith as something that returns those who practice it to the barbaric, uncivilised state African tribes were found in when white men first travelled to Africa and began enslaving those they found there. The justification then was that these people needed to learn to live like western cultures and so the atrocities they were put through by white men was for their own good, so too could we say that the films imply that this return to tradition will adversely affect modern black culture. These imagined transgressions are committed by black women specifically, not men, and so we must wonder why it is the black female who is expendable when it comes to suffering. | | Facing herself, the black female realises that all she must struggle against to achieve self-actualisation.

She must counter the representation of herself, her body, her being as expendable.

- bell hooks (1981, p65) | Bell hooks builds on this idea of expendable black women with her work reminding us that female slaves were not as valuable as male slaves, though they became attractive because of their tribal instinct to be obedient to superiors (1982, pp 15 - 17) - though slave masters were a far cry from the tribal leaders of their homeland. She also went on to reiterate how these women were brutalised in ways that men were not through rape and torture and the murder of young children to ensure fear and obedience from the mother.

Yet, if it was so important that these women become docile and allow themselves to be used for the gratification of white men; why are they then so expendable? Why, because they are not white women. White women would never be expected to suffer as such, and a white man certainly would not desire a wife who had been branded and beaten;whereas the less human black woman, with her exotic skin tone, her full lips and her big bottom, can be used in such a way despite all the similarities genetically to white women. Therefore, conclusively, whilst we can agree that the black woman is a woman just as much as a white woman; there is little evidence that a bodacious slave girl will ever be treated like a lady. Bibliography hooks, b. (1982). Ain't I A Woman? Black Women and Feminism. Boston, MA: South End Press. hooks, b. (1992). Black Looks: Race and Representation. Boston, MA: South End Press. Spivak, G.C. (1988). Can The Subaltern Speak. In Ashcroft, B., Griffin, G., and Tiffin, H. (eds) (1995). The Post-Colonial Studies Reader. (pp 24 – 28). London and New York: Routledge. Sojourner Truth: Ain't I a Woman Too? Retrieved on November 21, 2013, from Modern History Source Book, Fordham University: http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/sojtruth-woman.asp.Filmography Lemmons, K. (Director). (1997). Eve's Bayou [Motion Picture]. USA: Trimark Pictures.

Parker, A. (Director). (1987). Angel Heart [Motion Picture]. USA: Carolco International N.V.

| The idea of a black aesthetic stems from the fact that white culture (film, music, art etc) is produced by the middle class, educated elite; and so the black community creates its own identity by going back to its roots in folk lore and tradition.

New Black Aesthetic producers like Spike Lee criticise the middle class producers by attempting to create a more authentic view of black culture - although since these were often funded by white sources there is some question as to just how authentic this view of the life of African Americans can be. |  Spike Lee |

| Trading Places (Landis, 1983) is arguably the first in a long line of interracial buddy movies where two very different men join forces for whatever reason and find that despite their differences they are able to becomes friends.

This classic formula is successful time and time again because star names make up for often tired narratives, and comedic actors such as Eddie Murphy excel in these story-lines precisely because the narrative may not be as fresh - their comedic talent shines through and brings in an audiences despite any other shortcomings in the production. | |

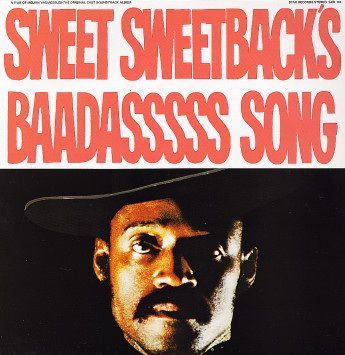

When Melvin Van Peebles made Sweet Sweetbacks Baadasssss Song (Peebles, 1971) he made the film for the empowerment of blacks and other minorities in America. Such a film had never been allowed before and Van Peebles had an almighty struggle to get the film made, let alone in cinemas. When Huey Newton, co-founder of the Black Panther Party , saw the film he was so moved by its message that he not only put pen to paper and wrote an extensive newspaper article on the production but also had the party adopt the film and made it compulsory viewing for all members, in all chapters across the United States. | | Despite this empowering start, other films aiming to cash in on Sweetback's success were more about using the black lead as a gimmick rather than expressing the original ideals of "sticking it to the man" and black power. Genre hybrids such as Blackenstein (Levey, 1973) and Blacula (Crain, 1972) fused the Hammer Studio's cheap but popular style with the idea of Blaxploitation, a term coined by pressure groups claiming that films such as Sweetback were not empowering to blacks because they often contained drug dealers and criminals - poor role models for black children growing up in a world where these were not the only jobs for blacks any more. Ed Guerrero described Sweetback as "Blaxploitation's high moment, its most sharply defined and prolific phase..." (1993, p71) and goes on to discuss how it was followed swiftly by more than fifity cheap imitations which very much lacked the message of the original. | | Alternatively there is a definite argument that these films still empower the black community as they began to rework the old black stereotypes. We still saw the fiery sapphire to a degree, but now she was the lead in these films, adding to the feminist movement at the time and still pushing forward the celebration of afrocentricity with new fashionable clothing and hairstyles.

As for the male leads, not all were criminals and drug dealers: many films such as Shaft (Parks, 1971) were police officers that were a little more rough around the edges than previously seen, endorsing these afro fashions and still keeping within the law. However, this audience participation in these styles is one of the reasons we must come back to the exploitation of blacks - these styles were designed and promoted by white studios to make money from fans of these pictures.

| Building on this idea that white directors suddenly realised there was a black audience to tap in to, we can see why blaxploitation boomed as a genre in film making even though most of the releases flopped at the box office. The problem was that the white directors, simply by being white, could not deliver what the black audience wanted to see. Though well documented, they hadn't actually lived the struggle of the black American and they had no cultural roots to draw from when writing characters, which resulted in more of the stereotypes that black film-makers were trying to dispel. This is another reason why blaxploitation must be considered exploitation of the race for the most part, because no matter how much black film-makers tried to show the truth of the black situation on film the white studios would always copy these ideas to make a fast dollar. Mathias Hanf made this point when he said that "the black audience, stung by the assassination of Martin Luther King, and increasingly uncomfortable with Poitier's polite and bourgeois persona now insisted on a new kind f screen hero; "A black, urban, poor male striking back at a system which had denied him basic rights and respect."" (2005, p7), and this proves once and for all that whilst the black community needed heroes, providing them with blaxploitation pictures did not give them the hero they wanted.

To conclude, early Blaxploitation films such as Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song (Peebles, 1971) can be considered empowerment because they were made with that idea in mind; however subsequent films, especially those made by white directors, were made to cash in on an ideal rather than to empower blacks and so these later productions can only be considered exploitation. Bibliography Gurerrero, E. (1993). Framing Blackness: The African American Image in Film. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Hanj, M. (2005). The Cluture of Blaxploitation. Germany: Druck und Bidung. Filmography Crain, W. (Director). (1972). Blacula [Motion Picture]. USA: American International Pictures.

Hill, J. (Director). (1974). Foxy Brown [Motion Picture]. USA: American International Pictures.

Levey, W. (Director). (1973). Blackenstein [Motion Picture]. USA: Frisco Productions Limited.

Parks, G. (Director). (1971). Shaft [Motion Picture]. USA: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

Van Peebles, M. (Director). (1971). Sweet Sweetback's Badass Song [Motion Picture]. USA: Yeah.

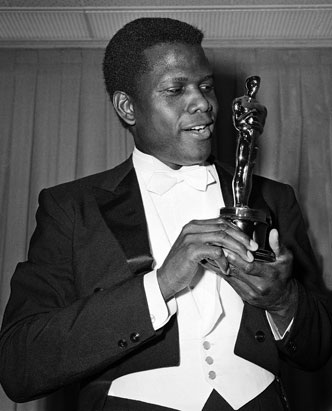

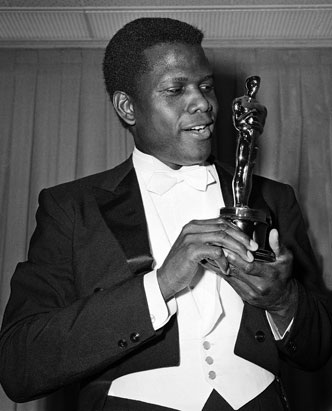

| The New Negro is a term that emerged during the Harlem Renaissance, coined by Alain Locke in his 1925 essay. The text called for African Americans to reject the old stereotype from the days of the plantations and embrace a new image, inspired by European thinkers, who's thoughts on the black race were far more liberal than the racist bile America preached so freely. |  No Way Out (Mankiewikz, 1950) | For generations in the mind of America, the Negro has been more of a formula than a human being ⎯ a something to be argued about, condemned or defended, to be “kept down,” or “in his place,” or “helped up,” to be worried with or worried over, harassed or patronized, a social bogey or a social burden. (Locke, 1925) In 1949 the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (the NAACP) met with Hollywood Studios in the hope of creating integration between black and white actors, and leading roles given equally to both on the basis of talent rather than skin colour. Hollywood accepted this idea since takings were plummeting due to the rise of television in the US at the time, and after the fight against fascism that was WWII ended America certainly could not pretend it held the moral high ground when the world had seen images of its mainstream abuse of blacks, and black soldiers themselves vowing not just to ""return from fighting" but to "return fighting" on behalf of "democracy." (Gates & Jarett, 2007, p8). This social revolution resulted in black actors being given more roles as figures of authority, with three dimensional character development and the opportunity to act alongside their white counterparts. These roles were a far cry from the racial stereotypes of old, painting blacks as non-threatening, non-sexual, middle class, conservative, dignified and loyal. | This is where the idea of "The Acceptable Face of Blackness" comes from. As the title of this blog post infers, this New Negro with his asexual and placid, but dignified characterisation makes us realise the true intentions of white directors bringing black leads in to their Hollywood productions. They wanted to show that they no longer held the opinions of directors such as D.W. Griffith, who's depiction of the predatory slave in his 1915 race movie classic Birth of a Nation (Griffith, 1915) still shocks to this very day. Instead they show that they accept the black man as part of white society as long as he adheres to their expectations regarding his dress, class and education. Namely, he must be at least more educated than the family of a young lady if he is to be allowed a relationship with her; or as we saw in No Way Out (Mankewikz, 1950), a black doctor must excel in his career far earlier than a white doctor would be expected to in order to be taken seriously in his profession. |  Sidney Poitier - Star of New Negro classics such as In the Heat of the Night (Jewison, 1967) and Guess Who's Coming to Dinner (Kramer, 1967), and the first African American to win an Oscar | Therefore, the white community can no longer be considered racist because they accept this figure under certain socially realist terms; though there could certainly be an argument for why a black man needs to prove he is worthy of white company at all. Nevertheless, Sidney Poitier and his famed New Negro movies definitely show that, ultimately, the New Negro black man is welcome in white society, given enough effort on his part; whereas those who do not adhere to this acceptable face most certainly are not. Bibliography Gates, H. L. & Jarett, G. (Eds). (2007). The New Negro: Readings on Race, Representation and African American Culture, 1892 - 1938. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Locke, A. (1925). Enter The New Negro. [Electronic Version]. The Making of African American Identity, Vol III. pp 1 - 6. Filmography Griffith, D.W. (Director). (1915). Birth of a Nation [Motion Picture]. USA: David W Griffith Corp.

Mankiewikz, J. (Director). (1950). No Way Out [Motion Picture]. USA: Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation.

| The Mulatto is a tragic figure because she is ostracised by all of society.

The black community will not accept her because she is ashamed of her blackness, and abandons her family and community in order to to pass as white.

In turn, the white community will not accept her once it is revealed that, despite her place skin tone, she is actually black in blood and in origin, and therefore cannot fully integrate in to their society. | |

According to Bogle "Hollywood film-makers demeaned and ridiculed the American Negro..." (2002. pp.101) and so American entertainment came a long way before it would allow a black actor to star in a film. Even in the days of minstrelsy, where white actors would use a mixture of burnt cork and face cream to darken their own skin, it was unheard of that a black actor would be the star. The first, it could be argued, was the character of Jim Crow; created by white actor Thomas Dartmouth "Daddy" Rice. The character was famous for his apparent black language and the Cake Walk - both intended by the whites to mock blacks, unaware that both were created by blacks to mock them!

| | The first truly black theatrical star was Bert Williams, a former minstrel who famously pretended to be thick and lazy with a strong southern drawl. In truth Williams was incredibly intelligent and spoke with a Caribbean accent, though his white audience loved his playing up to the black stereotype too much for him to allow his real self to shine through on stage and his black audience (segregated to the upper circle) enjoyed laughing at the white audience below who didn't realise the joke was on them.

In the early 1950's there emerged altogether eight musicals featuring all black casts. these were typically folk musicals featuring themes of the family and the home, and often set on plantations. However, these films were made in, and funded by, white film makers, and the lack of billing or contracts made film a very insecure career for a black artist. The first generation of black stars began to emerge around this time, and some are still household names even today.

Josephine Baker, straight out of a career on the vaudeville circuit, is most famous for her so called "banana dance." With her burlesque background it is unsurprising she became famous for dancing nearly naked on stage and became popular in France, where her mulatto heritage did not inhibit her desirability as it did in America. This later resulted in her abandoning her career and American nationality to become legally French and rise to stardom overseas. | | | | Character actor Lincoln Perry, better known as bumbling simpleton Stepin Fetchit, was the first black movie star to become a millionaire. as with Bert Williams before him, his white audience loved the black stereotype he portrayed and this resulted in massive success for Perry. | | Paul Robeson was, unlike other black actors, always seen as dignified and noble. He was a famous sports star, actor and baritone singer; and many of his roles involved him doing a musical number within the narrative. He admired communism in theory and was highly outspoken about his civil rights views, which led to him being blacklisted across the American entertainment industry. As a result of this, Robeson's star soon faded and he died in obscurity. | | | | Lena Horne was the first black female film star, probably because of her lighter skin tone. The real life tragic mulatto suffered at the hands of the studio's for her entire career, even being snubbed by MGM in favour of a white actress for her role of Julie when Show Boat (Sidney, 1951) moved from stage to screen. | It is often wondered if these old stars are just stereotypes, or if they are simply signifying to retain their popularity. Signifying can take many forms, but it is above all about improvising and thinking on your feet to stay in control in the face of adversity. This mental agility was often developed by young black slaves on plantations, where their older peers would gather round to watch as those involved would exchange boasts or insults to attempt to anger the other person. These usually came in the form of insulting the female family members of the young men, the ultimate insult that only the most practised in the art of signifying could withstand unphased. In doing this within their careers it could be said that the stars managed to somehow retain their identity whilst still conforming to the demands of the studio, and living with this duo of personalities is likely why the idea of the theoretical and physical mask rings true with so many. Arthur Knight tells us that "this is why blackface mattered and why it wasnt simply rejected out of hand by black actors, critics and audiences." (2002, p7). This mask is what kept the integrity of the actors, and kept the blatent racism in Hollywood from feeling too personal. After all, they just wear the mask. Bibliography Bogle, D. (1988). Toms, Coons, Mulattos, Mammies and Bucks. New York: Garland

Gates, H.L. (1988). The Signifying Monkey. pp 44 - 88. New York: Oxford University Press.

Knight, A. (2002). Disintegrating the Musical: Black Performance and the American Musical Film. North Carolina: Duke University Press

Filmography Kemp, J. (Director). (1948). Miracle in Harlem [Motion Picture]. USA: Herald Pictures Inc.

Sidney, G. (Director). (1951). Show Boat [Motion Picture]. USA: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc.

Stone, A. (Director). (1943). Stormy Weather [Motion Picture]. USA: Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation.

Whale, J. (Director). (1936). Show Boat [Motion Picture]. USA: Universal Pictures.

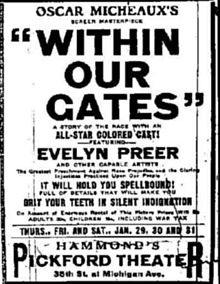

Race movies such as Within Our Gates (Micheaux, 1920) are a prime example of why, sadly, such films must be considered amateur. Simply because black film-makers had the odds stacked against them with their sub-par equipment and film-making knowledge compared to the white controlled studios, does not mean that these films can be considered the same quality as those made by such studios. It is worth noting that this film would not have been allowed past the scripting stage by a white studio due to its sobering content, particularly the scene where we see white men, women and eve children actively taking part in a lynching, however this does not excuse the poor quality of the film-making itself. | | Filmography Micheaux, O. (Director). (1920) Within Our Gates [Motion Picture]. USA: Micheaux Book and Film Company.

A case could be argued both for and against stereotyping in film; both largely depending on the purpose of said stereotyping. Put aside, if you will, the point of racism to consider the following ideas for a moment: Firstly, one who was to argue that stereotyping is a necessity in film making would undoubtedly make the point that without it the audience may be confused as to why a certain person was playing a certain character if they did not clearly represent such a person off screen. Many an argument has been made for this case even recently, when Johnny Depp was cast as the Native American character in The Lone Ranger (Verbinski, 2013) despite obviously not being Native American. Though slightly less obvious through the means of modern make-up and post-production, this is still the modern day equivalent of white actors smearing their faces with burnt cork to appear black in early cinema - namely, why not just get someone with the appropriate heritage to play the role? Because having a recognised name is more important than authenticity, that's why. This brings us neatly to my second point, that it could also be put that stereotyping is not necessary because the talent of the actor in question should overwhelm to such a degree that the audience recognises that they can play any character regardless of their physical attributes off screen. This makes it unnecessary to only ever cast Queen Latifah as a Mammy (although despite her being overweight, she is also often cast as a feisty Sapphire character) and have Will Smith resume his early role as the Trickster, or as he would put it, the Fresh Prince. Despite the fact that, as Stuart Hall says, it is human nature to classify and "classification is a very generative thing, once you are classified a whole range of other things fall in to place because of it." (1997) He goes on to say that classifying people is about maintaining a kind of social order, though of course implementing fixed categories would be impossible. To bring this to a close, even Stuart Hall, seemingly in favour of dispelling stereotypes, argues that it is necessary to a degree to categorise people in to different groups. Therefore it would seem that yes, stereotyping is probably a necessity in film-making. Bibliography Bogle, D. (1988). Toms, Coons, Mulattos, Mammies and Bucks. New York: Garland Filmography Borowitz, A + Borowitz, S. (Producers). (1990 - 1996). The Fresh Prince of Bel Air [Television Series]. California: The Stuffed Dog Company.

Jally, S. (Director). (1997). Race, The Floating Signifier ft. Stuart Hall. Massachusetts: Media Education Foundation.

Verbinski, G. (Director). (2013) The Lone Ranger [Motion Picture]. USA: Walt Disney Pictures.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed